The pending onslaught of electric trucks and SUVs—already underway with the Rivian R1T and R1S, and the Ford F-150 Lightning—has people thinking about emissions-free camping and RV life as something viable in the near future.

As we’ve underscored in the past with Tesla towing reports and other reality checks on range, taking on Davis Dam Grade with 11,000 pounds might be possible, but is it really doable as part of an enjoyable vacation?

Not surprisingly, potential shoppers for this kind of vehicle have high expectations—ones that might not be entirely in alignment with today’s battery and charging technology, at the desired price point.

Earlier this year several concept vehicles showed that the traditionally quite conservative RV industry isn’t sitting this one out. Between the Winnebago e-RV concept and the Thor Vision electric RV concept, some of the big players provided a potential sketch of what’s in the works—in quite different forms.

Winnebago e-RV electric motorhome concept

Winnebago e-RV electric motorhome concept

Winnebago e-RV electric motorhome concept

While the Ford Transit–based Winnebago e-RV has an 86-kwh battery pack and will provide a 125-mile range—enough to satisfy 54% of RV buyers, it claims—Thor Industries went in a different direction completely. Also starting with the Transit, it included a battery pack, a hydrogen fuel cell, and a solar roof, adding up to 300 miles of range.

Although at the time it seemed like a lot of complexity, Thor recently revealed study results that supported its approach. Its North American Motorized Electric RV study was conducted in December 2021, the month before the Vision. That study was based on 675 respondents who had either currently owned an EV or had some level of RV experience (owning, renting, camping, or borrowing) within the last 10 years.

Thor\’s North American Motorized Electric RV study

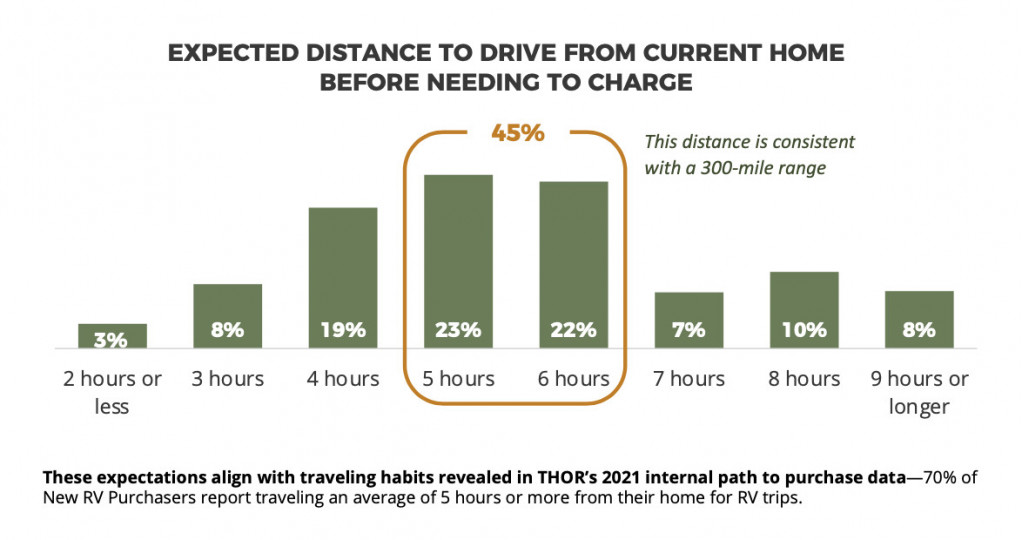

Its study—or really, a poll, from the sound of it—found that 97% expect to drive three hours of longer before charging. Nearly half (45%) of respondents said that they expected to drive five or six hours from home before needing to charge—a figure that Thor sees as a sweet spot, and roughly consistent with a 300-mile charge.

Nearly one in five saw that point being eight or more hours on a charge—suggesting a range of more than 500 miles. Although 300 miles could be a realistic target in a few years, the higher number is likely a physical impossibility given price and battery-pack weight constraints.

Thor Vision electric RV concept

The people who use such an electric RV would do so often, too. While many RVs in the U.S. sit unused for vast portions of the year, 47% of respondents to this survey said they’d use an electric RV at least once every two to three weeks—some at least once a week.

The most popular response for an expected charge time was in the 45-to-59 minute range, suggesting the need for DC fast-charging not just in products like this but as an infrastructure need, at campsites nationwide. It’s a big leap from the typical 240-volt, 30-amp outlets at U.S. campsites to fast-charge compatibility.

Surprisingly, 70% of respondents said that an onboard hydrogen fuel-cell system to help supplement or charge the battery would positively affect purchase intent. Although establishing more charging at campsites would be quite an infrastructure hurdle, distributing hydrogen or fuel cells sounds like an even bigger puzzle.

Airstream eStream electric camping trailer

In addition to the electric RV project, Thor earlier this year revealed the eStream travel trailer concept—an electric camping trailer that would essentially provide its own propulsion, carrying 80 kwh of battery capacity along and adding to acceleration and brake regen with its own motor system.

Alternatively, camper manufacturer Colorado Teardrops plans a version of its camper trailer that also brings extra batteries along for the ride, but without the propulsion system. You charge both up overnight, then at roadside breaks, it instead charges up your towing EV.

Colorado Teardrops Boulder EV camping trailer

Both of those solutions help solve the issue of driving range but underscore the need for serious, high-power charging infrastructure at campgrounds—and elsewhere, with physical layouts that work for RVs and trailers. Who will step up to deliver this? It’s another chicken-or-the-egg, all over again.